Bupropion is a unique antidepressant with FDA-approved indications for major depressive disorder1-32, seasonal affective disorder1,2, smoking cessation4, and as an adjunct to diet and exercise for chronic weight management in adult patients with BMI >=30 kg/m2 when co-formulated with naltrexone.5 Unlike tricyclic antidepressants, bupropion is a monocyclic aminoketone and in a pharmaceutical class by itself. Although often lumped with serotonergic SSRI antidepressants, it has limited serotonergic properties. The most significant side effect of bupropion is its risk of seizures.

Bupropion has been associated with seizures even at therapeutic doses and was removed from the market shortly after it was initially approved in 1986.6 Data showed that seizure risk was dose-dependent and highest in patients with eating disorders, previous head trauma, or epilepsy. Bupropion was reintroduced to the market 3 years later with label adjustments that included a lower maximum daily dose and contraindications for use in epilepsy, eating disorders, or head trauma. While these measures improved the safety at therapeutic doses, seizures continue to be a serious effect in overdoses.

As with other antidepressants, bupropion is commonly involved in poisonings. In 2014, antidepressants were the fifth most common substance class involved in human poison exposures reported to US poison control centers.7 Bupropion, specifically, was involved in 11,222 reported exposures, and moderate or major outcomes were reported in 1,453 exposures and death in 4 cases where bupropion was the only substance.7

Pharmacology and Pharmacokinetics

Bupropion inhibits the reuptake of norepinephrine and dopamine, and unlike many other antidepressants, it has little effect on serotonin reuptake.8 Bupropion shares structural similarities to stimulant drugs, including cathinone and amphetamine derivatives.

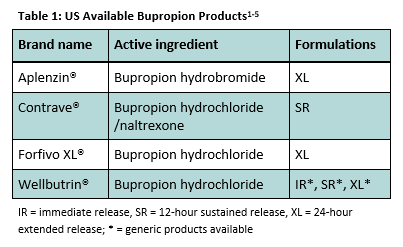

Bupropion is available orally as a hydrochloride or hydrobromide salt, in combination with naltrexone, and in immediate and modified release formulations (Table 1).

Bupropion concentrations peak in less than 2 hours for immediate release preparations, but take as long as 5 hours with the modified-release formulations.1-5 Its half-life is 21 hours. Bupropion has 3 active metabolites with half-lives ranging from 20-37 hours. The primary metabolite, hydroxybupropion, is formed in the liver through CYP2B6 and has a peak plasma concentration 7 times the peak of the parent drug.1-5,9

Adverse and Toxic Effects

Adverse effects, including dry mouth, abdominal pain, nausea, anorexia, myalgia, insomnia, dizziness, agitation, anxiety, tremor, pharyngitis, palpitation, sweating, rash, tinnitus, and urinary frequency, occur in greater than 5% of patients taking bupropion therapeutically.1-5 Manufacturer information reports seizures occur in approximately 0.1% of patients who take 300 mg SR and 0.4% who take 300 mg-450 mg IR.1-5

In a review of 7,348 immediate-release and sustained-release bupropion exposures reported to US poison centers between 1998 and 1999, clinical effects were documented in 2,247 (30.6%).10 The most common effects were tachycardia (30.0%), drowsiness/lethargy (22.6%), seizures (18.6%), agitation/irritability (14.8%), vomiting (14.1%), and tremor (11.8%). Single seizures occurred in 265 patients, multiple seizures in 133 patients, and status epilepticus in 19 patients. Five deaths were reported.10

Most patients who have a seizure experience a prodrome that includes tachycardia, agitation, tremor, and/or hallucinations. In a review of 385 intentional bupropion exposures reported to Texas poison control centers from 1998-1999 by Shepherd, 40 out of 41 patients (97.6%) experienced agitation, hallucinations, or tremor prior to their first seizure.6 In a 3-year study at 5 different poison control centers conducted by Starr, patients who seized after ingesting bupropion were more likely to experience agitation (29.7% vs. 12.5%, p. 0.045), tremor (40.5% vs. 17.5%, p. 0.005), and tachycardia (91.8% vs. 51.2%, p. 00005) when compared to patients who did not seize.11

The onset of seizures can vary widely in bupropion overdose and is likely dependent on drug formulation. In exposures reported to Texas poison control centers, onset time to initial seizure ranged from 1 hour to 14 hours post-ingestion (mean, 4.3 ± 3.2 hours).6 Sustained-release preparations accounted for 71% of these exposures.6 Looking at ingestions of the XL formulation only, Starr found that onset time to initial seizure ranged from 0.5 to 24 hours post-ingestion (mean, 7.3 ± 5.4 hours).11 Initial seizure occurred within 8 hours in 68% of patients, between 8 and 24 hours in 24% of patients, and with unknown timing in 8% of patients. Nearly half (49%) of the patients who seized experienced a second seizure with average onset of 9.8 hours (range 1.5-19 hours) post-ingestion.11

Severe cardiac toxicity is rare following bupropion overdoses. However, conduction disturbances (QRS prolongation, QTc prolongation), dysrhythmias, hypotension, and cardiovascular collapse have been described.12,13

Management

Decontamination may be appropriate in patients presenting soon after large bupropion overdoses. Activated charcoal may be considered within 1 hour of ingestion in patients who are not actively seizing or post-ictal who are able to protect their airway.15 Whole bowel irrigation may be considered in patients who ingest very large quantities of modified release preparations.16

Bupropion exposures require extended observations due to the risk of delayed onset seizures.11 Modified-release preparations are commonly preferred for their dosing convenience, and symptom onset does not correlate well with the pharmacokinetics of the parent drug but may be due to its active metabolites. This is especially true for the risk of developing delayed-onset seizures after a relatively asymptomatic period of 8 hours or more in overdose situations. The Utah Poison Control Center recommends monitoring patients at least 8 hours post-ingestion for immediate release bupropion and 24 hours post-ingestion for sustained and extended release bupropion and all self-harm attempts. If patients become symptomatic, observe until symptoms are resolved.

There is no specific antidote for bupropion, and management is supportive. Benzodiazepines are the drug of choice to treat bupropion seizures and should be strongly considered for patients with agitation, tachycardia, hallucinations, or tremor in order to prevent progression to seizures. Barbiturates and propofol may be considered for refractory seizures.17 Since drug-induced seizures are diffuse and have no identifiable seizure focus, phenytoin is less likely to terminate these seizures when compared to other sedative-hypnotic anticonvulsants.17

A baseline ECG and frequent vital sign monitoring should be performed on all patients who ingest bupropion. For all self-harm ingestions, patients should be placed on continuous cardiac monitoring, paying close attention to the QRS and QTc intervals. In the case of severe cardiac toxicity, intravenous lipid emulsion therapy may be considered, and consultation with a medical toxicologist is recommended.18

Summary

Bupropion is a unique antidepressant with an increased risk for seizures in supratherapeutic doses. Onset of seizures can be delayed 16-24 hours, necessitating prolonged observation times following ingestion of modified-release formulations. The Utah Poison Control Center is available at 1-800-222-1222 for toxicology consultation, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days per year.

Author: Taylor Rhien, PharmD, Certified Specialist in Poison Information and Kyle Murray, PharmD

Sources:

1. Wellbutrin XL® (bupropion hydrochloride) [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America LLC; Aug 2016.

2. Aplenzin® (bupropion hydrobromide) [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America LLC; Jul 2014.

3. Forfivo XL® (bupropion hydrochloride) [package insert]. Austin, TX: Edgemont Pharmaceuticals, LLC; Aug 2016.

4. Zyban ® (bupropion hydrochloride) [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; Jun 2016.

5. Contrave® (naltrexone hydrochloride and bupropion hydrochloride) [package insert]. La Jolla, CA: Orexigen Therapeutics, Inc.; Sep 2014.

6. Shepherd G, Velez LI, Keyes DC. Intentional bupropion overdoses. J Emerg Med. 2004; 27(2):147-51.

7. Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Brooks DE, et al. 2014 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers' National Poison Data System (NPDS): 32nd Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2015; 53(10):962-1147.

8. Stahl SM, Pradko JF, Haight BR, et al. A review of the neuropharmacology of bupropion, a dual norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2004; 6(4): 159-166.

9. Baselt RC. Disposition of toxic drugs and chemicals in man, 8e. Foster City, CA: Biomedical Publications; 2008.

10. Belson MG, Kelley TR. Bupropion exposures: clinical manifestations and medical outcome. J Emerg Med. 2002; 23(3):223-30.

11. Starr P, Klein-Schwartz W, et al. Incidence and onset of delayed seizures after overdoses of extended-release bupropion. Am J Emerg Med. 2009; 27(8):911-5.

12. Morazin F, Lumbroso A, Harry P, et al. Cardiogenic shock and status epilepticus after massive bupropion overdose. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2007; 45(7): 794-797.

13. Livshits Z, Feng Q, Chowdhury F, et al. Life-threatening bupropion ingestion: is there a role for intravenous fat emulsion? Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2011; 109: 418-422.

14. Thorpe EL, Pizon AF, Lynch MJ, Boyer J. Bupropion induced serotonin syndrome: a case report. J Med Toxicol. 2010; 6(2):168-71.

15. Chyka PA, Seger D, Krenzelok EP, Vale JA. Position paper: Single-dose activated charcoal. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2005; 43(2):61-87.

16. Position paper: whole bowel irrigation. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2004; 42(6):843-54.

17. Shah AS, Eddleston M. Should phenytoin or barbiturates be used as second-line anticonvulsant therapy for toxicological seizures? Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2010; 48(8):800-5.

18. Gosselin S, Hoegberg LCG, Hoffman RS, et al. Evidence-based recommendations on the use of intravenous lipid emulsion therapy in poisoning. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2016. Epub 2016 September 8.

ABOUT THE UTAH POISON CONTROL CENTER

The UPCC is a 24-hour resource for poison information, clinical toxicology consultation, and poison prevention education. The UPCC is a program of the State of Utah and is administratively housed in the University of Utah, College of Pharmacy. The UPCC is nationally certified as a regional poison control center.