Toxicology Case Files from the Utah Poison Control Center

Take Home Points

- Ingestion of caustic acidic or alkaline solutions may cause severe aerodigestive injury

- Endoscopy is indicated in any intentional ingestion or symptomatic patient

- Steroids may be helpful in preventing esophageal strictures in select patients

Case Presentation

A two-year old girl is found in the bathroom playing with a bottle of toilet bowl cleaner after parents hear her crying. Some of the product is around her mouth and she has a burn on her lip. After washing off the remaining cleaner, she is still crying and uncomfortable. Her parents call the Utah Poison Control Center and they are referred to the nearest emergency department for evaluation.

Caustics

Exposure to caustic agents either by ingestion, inhalation, or dermal routes can lead to serious morbidity and mortality. Caustics generally refer to substances at the extreme ends of the pH scale (<3 for acids and >11 for bases). As their name implies, these products cause serious soft tissue injury. Alkaline agents cause liquefactive necrosis while acidic agents cause coagulative necrosis. However this distinction is not clinically important as serious injuries occur with both types of caustics.

Common household products containing strong caustics include drain cleaners, toilet bowel cleaners, and oven cleaners.

In 2019, there were more than 8,000 exposures to caustic drain and toilet cleaners reported to US poison centers .1 The large majority of these exposures occurred in young children. While fatalities are rare in children, serious long term effects such as esophageal strictures may occur.

Evaluation & Management

Any child exposed to strongly acidic or alkaline products requires evaluation in an emergency department given the possibility of serious aerodigestive injury.

Decontamination measures should be limited to rinsing exposed skin with water. If the patient is able to cooperate, water may be used to rinse out the mouth. More aggressive measures including attempts at neutralizing the caustic are not advised. Activated charcoal is not effective as systemic absorption is not of concern, ionic compounds do not adsorb to charcoal, and the activated charcoal would obscure tissue evaluation at endoscopy.

Airway compromise is possible. Standard measures for airway management are recommended as needed including racemic epinephrine and steroids or even endotracheal intubation.

The most serious complication of caustic ingestion is esophageal or gastric perforation which may lead to mediastinitis and death. Patients with perforation are acutely ill and the clinical presentation is not subtle.

Fortunately most children with exploratory ingestions of caustics are not severely ill at presentation. The main management question is whether early endoscopy (ideally within 12-24 hours) is indicated to evaluate for esophageal and gastric injury.

A common question about endoscopy is how it will change management. The long term complication of greatest importance in caustic ingestion is esophageal stricture. Identification of significant esophageal injury may prompt treatment to prevent stricture formation and facilitate close follow up for diagnosis and treatment of esophageal stricture. Those without significant injury may be discharged, shortening hospital length of stay.

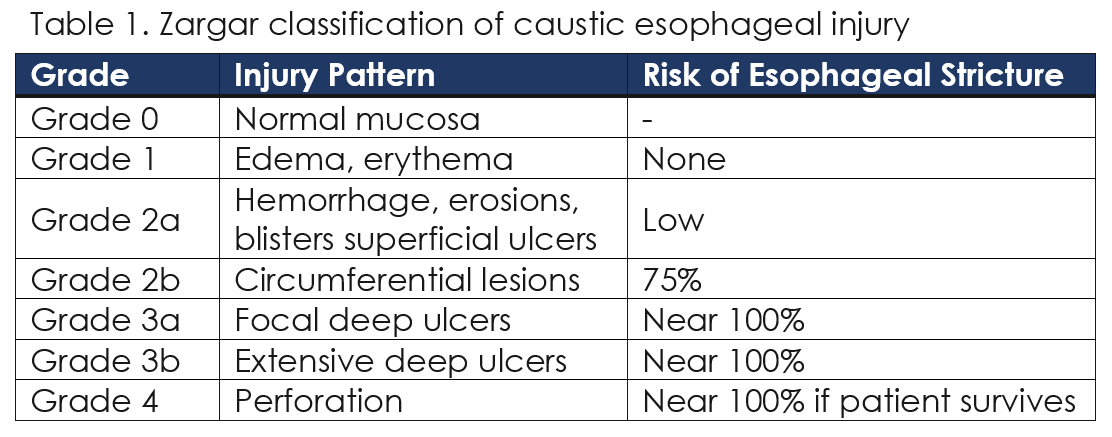

Esophageal injury in caustic ingestion is graded according to the Zargar classification (Table 1).

Patients with 2b or more severe injury may require placement of a nasogastric tube or stent to facilitate feeding and prevent strictures.

Medical therapy may also help prevent strictures in patients with grade 2b injury. A randomized, controlled trial studied pediatric patients with grade 2b injury after caustic ingestion. The study group received methylprednisolone dosed at 1 g/1.73 m2 for 3 days in addition to usual care (ranitidine, ceftriaxone, and total parenteral nutrition). Rate of stricture formation was 10.8% in the steroid group and 30% in the control group (p = 0.038).2

Steroid therapy is not recommended for patients with minor injury (2a or less) as the risk of stricture formation is very low. Conversely, more severe injuries will invariably develop strictures and steroid treatment may impair response to infection related to perforation. Antacid therapy with H2 antagonists or proton pump inhibitors is reasonable though there is no evidence for benefit.

It is very difficult to predict which patients with accidental ingestions will have significant injury at endoscopy. Lack of caustic burns to the face, lips, or mouth does not exclude more distal injury. Children with an accidental ingestion that are asymptomatic, tolerating normal oral intake, and have no oropharyngeal injury are unlikely to have significant esophageal or gastric injury.3,4 However, in any cause of caustic ingestion, consultation with a poison center or endoscopist is recommended to determine need for further evaluation.

Case Resolution

In the emergency department the patient is crying but consolable. She has a small burn to her lip but does not appear ill. She refuses to eat a popsicle or drink juice. Endoscopy is performed and reveals a grade 2a esophageal injury. Her diet is advanced and she is discharged home with a short course of famotidine.

References

-

Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Beuhler MC, Spyker DA, Brooks DE, Dibert KW, Rivers LJ, Pham NPT, Ryan ML. 2019 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers' National Poison Data System (NPDS): 37th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2020 Dec;58(12):1360-1541. PMID: 33305966.

-

Usta M, Erkan T, Cokugras FC, Urganci N, Onal Z, Gulcan M, Kutlu T. High doses of methylprednisolone in the management of caustic esophageal burns. Pediatrics. 2014 Jun;133(6):E1518-24. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3331. PMID: 24864182.

-

Crain EF, Gershel JC, Mezey AP. Caustic ingestions. Symptoms as predictors of esophageal injury. Am J Dis Child. 1984 Sep;138(9):863-5. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1984.02140470061020. PMID: 6475876.

-

Gorman RL, Khin-Maung-Gyi MT, Klein-Schwartz W, Oderda GM, Benson B, Litovitz T, McCormick M, McElwee N, Spiller H, Krenzelok E. Initial symptoms as predictors of esophageal injury in alkaline corrosive ingestions. Am J Emerg Med. 1992 May;10(3):189-94. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(92)90206-D. PMID: 1586425.

Author: Michael Moss, MD, Medical Director, Utah Poison Control Center

ABOUT THE UTAH POISON CONTROL CENTER

The UPCC is a 24-hour resource for poison information, clinical toxicology consultation, and poison prevention education. The UPCC is a program of the State of Utah and is administratively housed in the University of Utah, College of Pharmacy. The UPCC is nationally certified as a regional poison control center.